Historical Instincts, Memory, and Time

Historical Instinct of Cultures in Oswald Spengler's Philosophy of History

Every specific culture develops its own perception of time, organ of memory and conception of history. Spengler found a connection between a culture’s method of disposing the dead and its conception of time, historical instinct, and collective memory. Spengler’s philosophy of history adopted a relativistic approach to cultures, that is a treatment that viewed each culture as a separate monad, each possessing its unique forms from art, to science, architecture, urban planning, religion, and even funerary practices. In fact, one of the earliest indicators of a new rising culture is the invention of a new method of disposing the dead. The Egyptian culture for instance was oriented towards death — the afterlife, and the culture as a whole reflected this specific objective and fascination with the afterworld. Their practice of mummification, that is, to preserve the body of the dead, reflected a historical instinct that cares for the past and future, yet negates the present, for the mummification of a body is an affirmation of death and the afterlife. This is juxtaposed with the Indian culture’s method of burning the dead, which is in essence a rejection of death, as embodied by the concept of samsara—reincarnation, and a negation of time. This Spengler associated with the purely ahistorical soul of the Indian culture – that is comparable to a collective form of amnesia – perfectly represented by the Hindu concept of maya, that life is an illusion. Spengler argued that all facets of a culture emanate from one main idea that represents the cultural ethos, in the case of Indian culture the concept of maya gives birth to the mathematical concept zero—0, the mathematical embodiment of the Indian concept of the void or nothingness.

Indian man forgot everything. But Egyptian man forgot nothing

Spengler argued that the historical instinct of Faustian Western culture is similar to that of Egyptian culture, since it also reflected a care for the past and future. With the West, we see the rise of archaeology and even cabinets of curiosity which eventually evolved into museums today. The Greco-Roman culture for instance did not produce a Petrarch to excavate the ruins of Troy, due to their lack of historical instinct and their emphasis on the present. The dynamism of the Faustian West, in its obsessive quest for infinite space — and time, fuses the care for the past and future with the present. Unlike the Indian negation of time and space, the Greco-Roman obsession with present and now in Euclidean space, and the Egyptian affirmation of time and space, the Faustian West synthesized space and time as embodied today by the space-time continuum in the theory of relativity. To the Western man space and time were no longer separate as seen in Euclidean Greco-Roman conceptions of space. This Faustian urge is also seen further in the West’s invention of accurate and intricate spatial representations of time with the Germanic clock. The Faustian obsession with time according to Spengler can be traced back to their clock towers and belfries, which have evolved to pocket watches, wrist watches, and different forms of clocks across Western culture’s history and present-day. Concerning this Spengler said:

Amongst the Western peoples, it was the Germans who discovered the mechanical clock, the dread symbol of the flow of time, and the chimes of countless clock towers that echo day and night over West Europe are perhaps the most wonderful expression of which a historical world-feeling is capable. In the timeless countrysides and cities of the Classical world, we find nothing of the sort. Till the epoch of Pericles, the time of day was estimated merely by the length of shadow, and it was only from that of Aristotle that the word cbpa received the (Babylonian) significance of “hour”; prior to that there was no exact subdivision of the day. In Babylon and Egypt water-clocks and sun-dials were discovered in the very early stages, yet in Athens it was left to Plato to introduce a practically useful form of clepsydra, and this was merely a minor adjunct of everyday utility which could not have influenced the Classical life-feeling in the smallest degree.

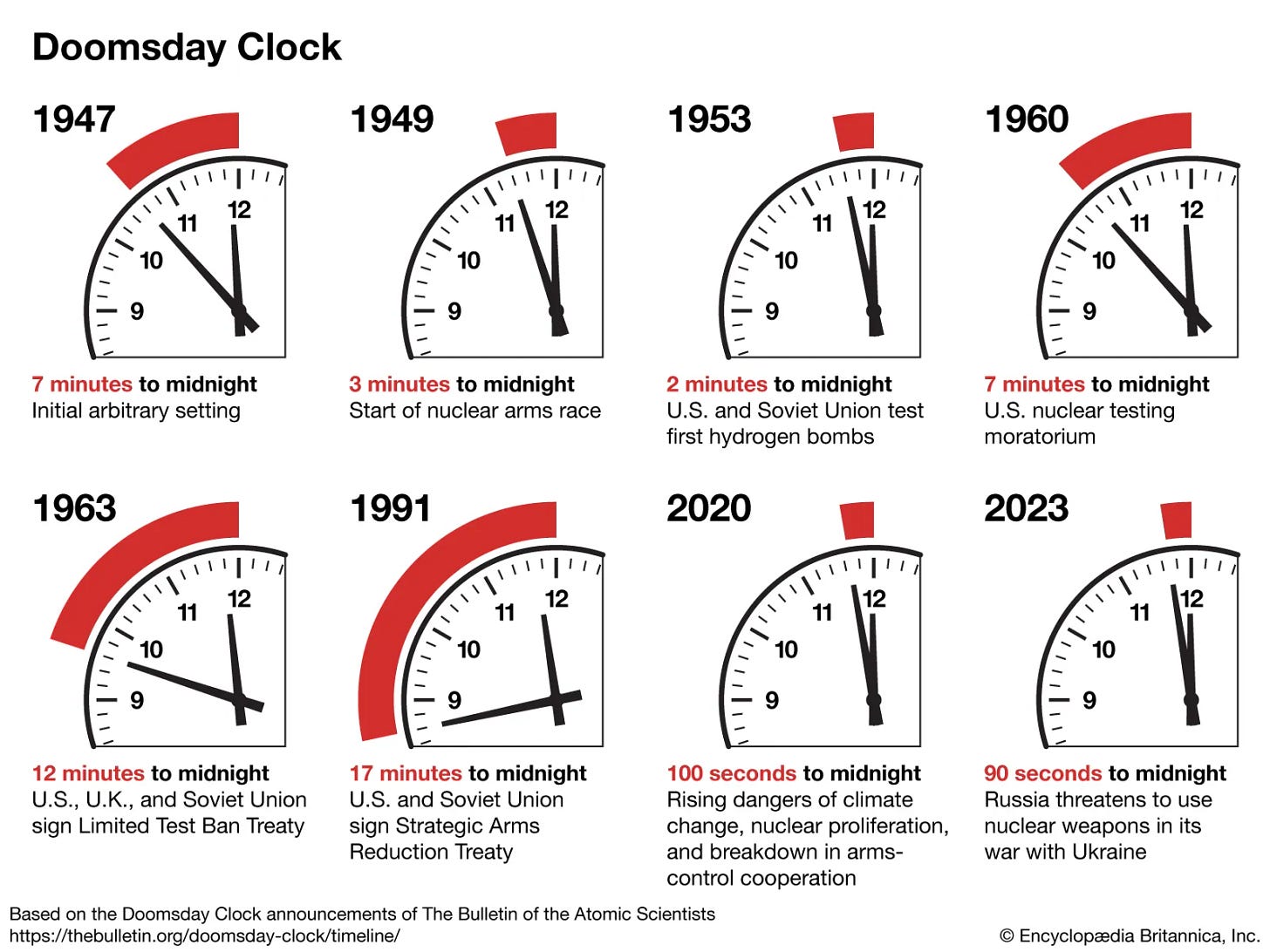

This Western Faustian obsession with time has expanded to a degree that scientists of the Manhattan project had created the Doomsday Clock a symbolic representation of the probability of a human-made apocalypse—midnight. Spengler alluded to the eschatological significance of the Western Gothic obsession with time, today, it is 90 seconds to midnight on the infamous Doomsday Clock, the closest it has ever been since its inception.

As previously mentioned, the funerary practices of a culture best reflect the historical instinct of a respective culture. With that said, regardless of the different historical instinct and organ of memory within every culture, individuals of all cultures share a similar trait which is crucial to grasp when questioning the epistemological foundations that form the cosmology and historical thought of a respective high-culture. That component is the fact that man is a being that is awake and in focus. A culture and man’s waking consciousness forms two main pictures, world-as-history and world-as-nature. The former utilizes critical understanding and “it has the eye under command, the felt pulsation becomes the inwardly imagined wave-train, and the shattering spiritual experience becomes pictured as the epochal peak”. Within the latter intellect rules, and “its causal criticism turns life into a rigorous process, the living content of a fact into abstract truth, and tension into formula”. The historical outlook emphasizes on the relation between the macrocosm and microcosm, and demotes knowledge into a simple supplement. In the faculty of memory, an individual (as macrocosm) views a specific event (as microcosm) based on the rhythm of his own existence. However, in the science or nature picture, “the chronological element tells us that history, as soon as it becomes thought history, is no longer immune from the basic conditions of all waking consciousness”. Experimentation and observation, within the realm of science and nature, necessarily enforces the practitioner to adjust their position in relation to the temporal world. This position of extreme detachment severs the connection between the subject and experimenter in order to establish valid causal criticism, which is a basic tenant of the scientific method. That said, this position results in an impersonal point of view where one tends to develop a forgetfulness in relation to temporality, destiny and history. The history picture stands in strong contrast to this, whereby:

Every man, class, nation or family sees the picture of history in relation to itself. The mark of nature is an extension that is inclusive of everything, but history is that which comes up out of the darkness of the past, presents itself to the seer, and from him sweeps onward into the future. He, as the present, is always its middle point, and it is quite impossible for him to order the facts with any meaning if he ignores their direction – which is an element proper to life and not to thought. Every time, every land, every living aggregate has its own historical horizon, and it is the mark of the genuine historical thinker that he actualizes the picture of history that his time demands.

To Spengler each culture has their own “world-history” and it is the job of the historian to determine what the historical thought of each culture is, what themes dominate the world-history of a respective culture and how to detach themselves from the collective historical instinct of their own culture. Through total detachment, the objective of the historian is to outline the shape of world-history without succumbing to the power of any culture’s unique historical-picture. The development of a culture’s historical instinct could be comprehended when compared to the child’s comprehension of his surrounding environment and the transformation of that understanding upon aging and confronting the vast city and its large populace. As a child, the terms people, country, nation, state and culture are meaningless and inconceivable, meaning is given to everything within their respective visual field only, namely, family, house, street and neighborhood. This youthful temperament is similar to the primitive culture’s, as well as the Greco-Roman culture’s, historical instinct, narrow and limited, dominated by “the drama of birth and death, sickness and eld; the history of a passionate war and passionate love, as experienced in himself or observed in others; the fate of relatives, of the clan, of the village, their actions and their motives”. After surpassing the stage of childhood, adulthood widens the visual horizon, the concepts of state, race, people, nation, countries and land are now intelligible. The youthful picture measures history in years, the mature picture in centuries. The secondary picture is the realm of historical tradition, and this picture, for Western man, is when history begins, and where history ends for the Classical conception of history. The picture developed by the culture is based upon the essence and spirit of the respective culture. For the Indian culture, history is non-existent, life in itself is an illusion – there is no space for a historical instinct in this unique culture. When observing Egyptian man, history’s journey begins in Duat, death or the afterlife, in accordance with the Egyptian conception of life, leading to a powerful faculty of memory as evident with the deliberate choice of durable material within the their longstanding megalithic structures (the great pyramids of Giza) and sculptures, as well as their preservation of the dead (mummification).

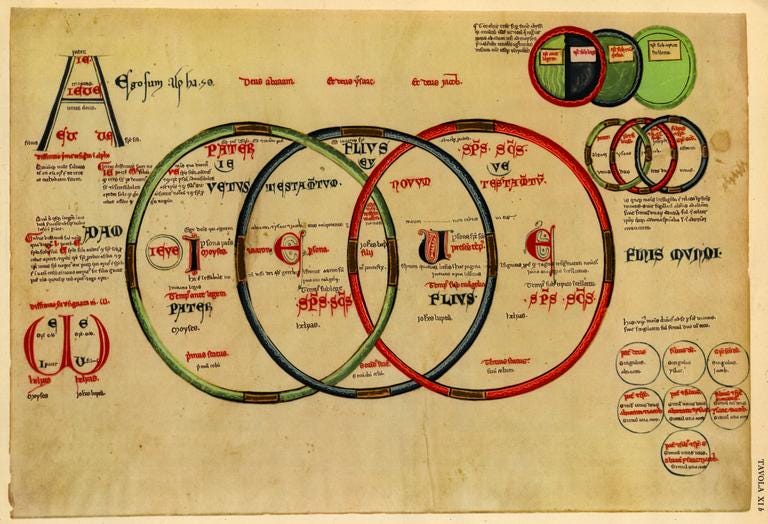

Past the secondary picture of history is the collective history of plant life, animals, landscape and the universe. To Spengler every living being comprehends destiny and history in relation to itself, and he argued that the Western historians’ conception of world-history is extremely different than that of historians within the zenith of Arabian and Chinese culture’s. An objective study of a specific historical era could only proceed when the historian is distant from that respective time period and is radically disinterested in the politics of that region presently and within the past. Hence why Western historians “cannot judge of or describe even the Peloponnesian Wars and Actium without being in some measure influenced by present interests”. The materialistic conception of history is an example of a historical lens which suffers from this limitation in an extreme manner according to Spengler. When comparing the different history-pictures within different high-cultures, it becomes apparent that the Classical and Indian culture share a similarity which makes them distinct from Arabian, Chinese and Western cultures. The former possesses a narrow horizon when compared to the wide horizon attained by other cultures. For the Arabian-Magian historical picture, we can witness a wide horizon within Judaic and Persian historical thought, which was broad enough to include the legends of creation as well as an eschatology which expands towards the future. The Egyptian and Chinese historical pictures possess a wide horizon embodied in their extended chronologies of dynasties. When exploring the Western Faustian historical picture, it becomes apparent that the picture is exported from Magian lands through the Western church and further developed by the aforementioned Joachim of Floris when he divided world-history into three aeons each symbolically representing the three forms which make up the concept of the holy trinity, namely, father-son-holy spirit.

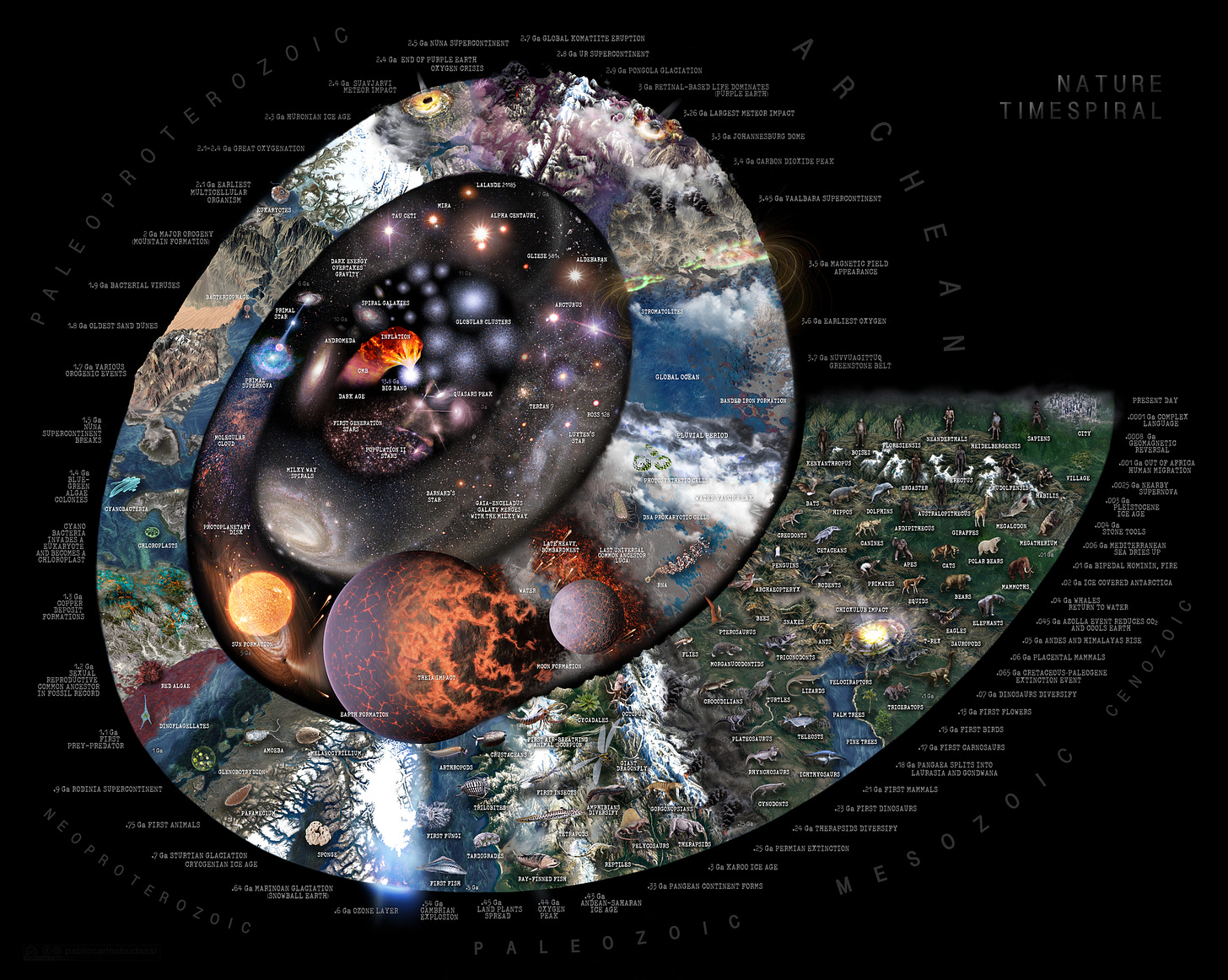

At the materialistic scientific phase of Western history, and following the professionalization of the discipline, these three time periods were replaced by the tripartite periodization model, ancient-medieval-modern. Moreover, owing to the Vikings, Crusaders and 15th century explorers, who ventured through far lands (Iceland, East Asia and the Americas) through harnessing the Faustian spirit and feeling of infinite space, the Western historical and geographical horizon was significantly broadened. One could also argue that the discovery of the poles, as well as the space race, could alter our modern historical picture and perhaps considerably broaden the frontier of our perception of history. Perhaps the newly emerging field of big history is a direct and logical result of this geographic and planetary expansion. Although, Spengler initially groups the historical picture of all cultures into narrow and wide outlooks. He eventually separates the Western picture from the other cultures that possessed a similar broad historical horizon. This distinction becomes clear when exploring the notion that world-history and the history of humans are not detached within the historical picture of most cultures. In other words, “the beginning of the world is the beginning of man, and the end of man is the end of the world”. Spengler argued that Western culture’s Faustian yearning for infinite knowledge separates these two historical subject matters. Thanks to breakthroughs within the fields of geology and paleontology, human history has become nothing but an almost insignificant episode within the vast history of the world. One would assume the Western culture’s dissection of Earth’s history, and reduction of human history into an insignificant mote of dust, would satiate the Faustian craving for the infinite.

But that is not the case, following developments in astronomy, the history of our Earth and Solar system is now trivial when placed against the millions of planetary systems across the universe. Western culture obsession with dissection is extended to include not only living forms but the overarching history of the universe and Earth. Now numerous historico-geographic planes exist, in order to explore these separate, albeit somewhat overlapping, planes we witness the emergence of several sciences with what Spengler terms “historical characteristics”. Of these we have astronomy, geology, anthropology and biology, each outlining the stories of the stars, earth’s crust, man and life respectively. Lastly, we have what Spengler designates as the “highly developed specialty of the West”, namely, biography outlining the story of the individual. This field embodies the same essence which developed the purely Western art form of portraiture, where history is “captured in a moment”.

Pardon the ignorance, but has the Big-Bang theory, leading to the second to last image used in the article, been proved?