Spenglerian Optimism: A Re-Imagination of Spengler's Philosophy of History

In the following essay, I provide a thorough explanation of Spenglerian Optimism through discussing the primordial forms of speculative philosophy of history across time, and where we could locate Spenglerian Optimism amongst the different forms of philosophy of history that have existed in the past. Moreover, I go through some of the ideas presented by Stephen Clark, who coined the term in question, and his critique of Spengler’s extreme pessimism concerning the rise of a new high-culture. The essay also explores some powerful examples of Spenglerian Optimism that have been published on Substack, more specifically,

’s recent contribution on the topic, titled “Aegean Civilization”. Finally, the essay describes the different scenarios Spengler provides beyond the decline of the West, and how this shapes the project as a whole.Stephen R. L. Clark’s paper introducing the concept of “Spenglerian Optimism” begins with a reaffirmation of Oswald Spengler’s pessimism, to the author of The Decline of the West (1917), the future is one of imminent decline, as Clark argued:

Our future, the future of “Faustian” humanity, can only be a long-drawn-out decline into a culturally stagnant, caste-divided, irreligious, inconsequential order of “fellaheen”.

This pessimism was not only unique to Spengler, but permeated within the rest of the episteme in Western culture, Wittgenstein, Blish, Kerouac, Toynbee, Chesterton, and Yeats, all shared this sense of pessimism and a bleak outlook for what the future holds. Yet, as Clark pointed, and I shall expand on here, this specific sociocultural phenomenon in itself, this sense of despair and pessimism during the 20th century, was not observed beyond the West, it was a uniquely Western phenomenon. Greg Swer had recently mentioned how Spengler himself argued for the relativity of his own theory, not only was history relative, but also truth, philosophy, and also his own specific philosophy of history — relevant to a specific place, time, and perhaps culture. This extreme relativism, combined with a quasi-positivism, is what Swer had called the “comparative paradox”. But what does this mean to us today a century after Spengler had published his philosophy of history, and future, in The Decline of the West (1917). This reveals a profound realization: the relativity of knowledge, and historicity of all phenomenon, combined with directionality (forward movement) of historical time, and our present gift of hindsight, could mean that Spengler’s philosophy of history could be amended — adjusted to a different time, culture, and new possible historical futures. As Clark mentioned, the Western civilization, which he and Spengler are both a part of, is not the rest of humankind: first, this means that even though the West is dying, it can still hope to “achieve great things”. Second, and more importantly, “Even if the Faustian Culture were entirely moribund there may already be another more youthful Culture beginning to find its Springtime”. Finally, even if these alternative Cultures—futures, are not currently present, they could appear spontaneously before our eyes. Moreover, Spengler’s philosophy of history as a whole emphasizes the theme of tragedy when witnessing history unfold through the rise and fall of cultures. This pessimism, which I have discussed in previous papers, is quite profound, precisely because the tragedy seems to close with an ultimate tragedy, which Spengler attributed to the rise of modernity — that is, modernity as an anti-cultural force. Farrenkopf, who has written extensively about Spengler’s work, has noticed this pessimism grow in Spengler as he grew older. Spengler could not help but notice the mechanization of the Earth, distorting its very face, with its animals, plants, and even human tribes and nations. The Goethean methodology Spengler deploys within his world-history, is one that focuses on the organic, plant-like, development of high-cultures, as seen in Goethe’s Metamorphosis of Plants (1790). Every culture emerges from a specific homeland, of which it has an intrinsic connection to, hence why the prime symbol of every culture is developed through the connection between a specific people and their own land — their unique ecological origin. Prior to modernity, these specific “ecological origins” were fertile, and untouched, thus, capable of giving birth to their respective cultures. Modern industrial society, however, has caused a sort of ecological deterioration, as seen with industrial society’s war with nature, at a deeper level, the lands could now also possibly not be capable of producing another high-culture, precisely because of the mechanizing effects of modernity, its expansiveness and transformative implications. When viewed metaphysically, this is quite a scary realization, if true, since the teleological development of Spenglerian high-cultures would come to an end, and the Earth — life — would have no purpose for the continued existence Man, especially in his hyper-modern anti-natural form. Spengler predicted the end of man, through a natural cataclysm, and even when he absorbs linearity—directionality, his cyclical philosophy of history is transformed into a spiral, which spirals upwards into the ultimate tragedy — to a crescendo, an apocalyptic end as a result of Man’s war with nature. If, however, by some miracle, industrial society — modernity as a whole, collapses, then Man could have another chance to give birth to new cultures that could have it as their sole purpose to heal this severance with nature, the spirit, and life.

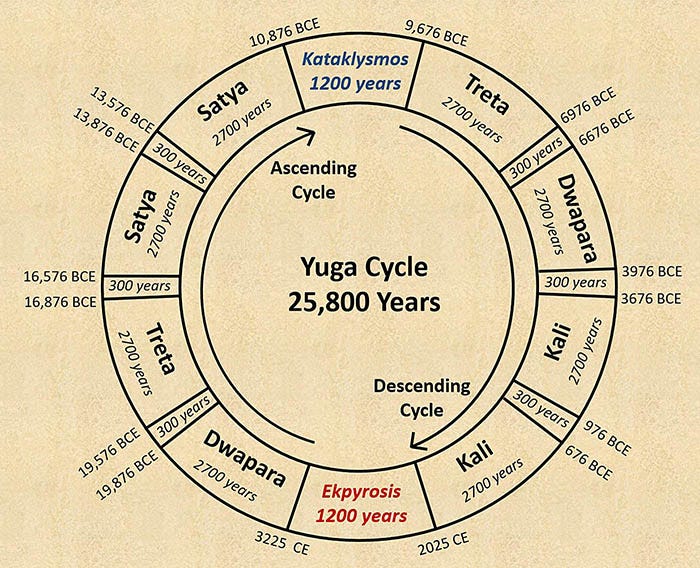

The purpose of my project, is to allow us to imagine these possible futures, philosophies of history, to me, are basic human concerns. Philosophizing about the nature of history—time, patterns in history, its directionality, its meaning, and values, are natural to every human. But more than that, every specific philosophy of history is a different vision for a possible future, and his its own unique social, political, ecological, technological, and economic implications. This explains the last, and perhaps most original, element within philosophies of history, its predictive elements and aspirations. The purpose of my own project, is to produce optimistic visions of Spenglerian philosophies of history with the sole purpose of producing visions that would lead to the birth of new human cultures, revive older petrified cultures, heal sickened cultures, and re-discover lost ones. During the past four years I have explored the vast literature on the development of philosophy of history across time, and in doing so I have noticed that philosophy of history, as a modern mode of knowledge, finds its origins in the intersection between apocalyptical-eschatological traditions, cosmologies and cosmogonies, and mythical grand-narratives. Hence why Augustine is seen as one of the first examples of a speculative philosopher of history across time, and of course there are many other examples, such as the Hindi Yuga Cycles, Monotheistic eschatological narratives, and even Greco-Roman cyclical conceptions of time as seen in the works of Hesiod and Plato for instance. That all being said, as Karl Lowith has pointed out in his work on the development of philosophy of history across history, namely, Meaning in History (1949), there seems to be perennial constants, or models, at play here, a cyclical pagan conception of time, perfectly embodied in the ancient symbol of the Ouroboros ( ⥀ ) which finds its expression in the Yuga cycles and Greco-Roman cyclicality, and the Monotheistic idea of eschatological directionality ( → ), as seen in Judeo-Christian-Islamic eschatological narratives. A third type eventually evolves out of the Enlightenment according to Lowith, which is essentially a modern inversion, or secularization, of the monotheistic Judeo-Christian-Islamic notion of eschatological direction. This third position is what we would today call the linear-progressive ( ↗ ) secular vision which is essentially inseparable from the spirit of modernity, if it even has a spirit, it is however a force, clearly, and a force to be reckoned with … unfortunately. The 20th century has witnessed, in my judgement, a synthesis of the two older, and more organic conceptions of time as a result of the enforcement of an inorganic-artificial linear notion of time embodied by the modern idea of linear-progress. This new conception is that of a spiral conception of time, which affirms the cyclicality of nature—space, what Spengler had called “world as nature”, and the directionality of history—time, of gradual organic progression in the Herderian sense of the term, rather than the Enlightenment progress, which is a reflection of the other realm, and perhaps the most dominant realm for us humans, the realm of historical-time which Spengler called “world as history”. The spiral is the final form that Spengler’s philosophy of history takes, and it merges perfectly the realms of time and space into one, not the Einsteinian flawed notion of spacetime, but the real synthesis of the realms of space and time that dominate what Kant had called the phenomenal and noumenal worlds, spatially represented by the symbol of the spiral— 𖦹 . The spiral conception of time is the guiding principle of the emerging paradigm which negates and transcends the outdated and currently dominant materialistic scientific paradigm. Thus, it was only natural that Karl Popper and Isaiah Berlin vehemently attacked speculative philosophies of history as a whole, ridiculing the notions of pattern, meaning, and directionality in history, for they were adherents to the worst forms of the Enlightenment conception of progress that was materialist in every sense and devoid of any spirit. Leading to a negation of time itself, a flawed conception of the past, and history. Both Popper and Berlin instead preferred a hubris filled scientificized form of history, in the form of an advanced sociology, or social dynamics, paired with the fields of social engineering and social physics, where the human is reduced to a simple cog or battery within a larger Frankenstein-like machine, an abomination of a culture — hyper-modernity. To move beyond such conceptions, an alternative paradigm emerges with the works of Karl Jaspers, Oswald Spengler, Rudolf Steiner, Rene Guenon, and other thinkers that have worked around the periphery of the dominant corrupt modern paradigm. Today however, as the outdated paradigms are exhausted, alternative paradigms emerge to fill their place, and the spiral paradigm will definitely emerge as one of the dominant paradigms out of many — leading to new possible futures. However, the upward-rolling spiral that Spengler envisioned, as opposed to the Hegelian Western moving spiral, cannot be deployed properly when combined with a purely pessimistic position. I do not usually, or perhaps ever, say that Spengler was wrong, indeed, even when it comes to his own extreme late pessimism, he was not wrong at all. For Spengler was a human after all, and one thing that many Spenglerians tend to forget, is this specific fact. A position of Spenglerian Optimism is thus only possible through humanizing Spengler, moving beyond the eternal death-stare of Decline that he is today known for. As humans, when exploring, or appreciating, Spengler’s own life as a human, we are faced with an individual of immense depth, but also facing an entrenched traumatic experience that perfectly explains how he had created such a profoundly complex and creative philosophy of history. However, it is our duty today, with the blessings of our own hindsight, growing up in an age of relative stability, and currently at the threshold between that stability and a return of history with all its chaotic vicissitudes, to liberate Spengler’s philosophy of history from its natural pessimism of its own relative zeitgeist.

Clark reconciles the doomsayer in Spengler, who affirms decline, with the optimistic cultural relativist, by arguing that if we were to take Spengler’s philosophy of history seriously we would realize that universalizing the Decline is in itself a symptom of a culture in its civilizational stage or winter period. Whether we do so in a Spenglerian manner, or Fukuyama’s “End of History” thesis, both arguments are true but cannot be applied to all human cultures. In Clark’s words, “The claim itself epitomizes Spengler’s ‘Civilized’ humanity”, and thus, the future opens up once more, concerning the future and present Spenglerian cultures, Clark said:

We cannot know what new spirit or image will awaken to entrance and animate humanity, what “rough beast,” in Yeats’s terms, is “slouching toward Bethlehem to be born” (whether for good or ill), nor even what new thought will reconstruct our own science or our society.

Clark also quotes Wittgenstein’s own argument concerning these possible futures, which he argued in a quite Spenglerian manner:

When we think of the world’s future, we always mean the destination it will reach if it keeps going in the direction we can see it going in now; it does not occur to us that its path is not a straight line but a curve, constantly changing direction.

To Clark, Spengler’s own philosophy of history is in itself intrinsically optimistic concerning the possibility of new human cultures beyond the Faustian West, as Spengler said, all cultures emerge from the sleep of the “ever-childish humanity”, as a “form from the formless, a bounded and mortal thing from the boundless and enduring” — in the words of William Irwin Thompson, a conscious expression of the unconscious. These cultures to Spengler bloom on the soil of an “exactly-definable landscape, to which plant-wise it remains bound”, indeed they have done so across world history. Yet, how many of these lands still remain fertile? how many lands and seas, in the vastness of our planet, with all its continents and oceans, have still not expressed their own spirit and forms? What of the Siberian and Eurasian steppes and plains? The Arido-American plane? What of the Polynesian islands in the Pacific Ocean, and the Far Eastern archipelagos? Surely, humanity still has the spiritual and organic capacity to live — to give birth to a new culture and resume our trajectory in the spiral of historical time. The pessimism about the future, clearly stems from the existential crisis brought about by modernity. Spengler was aware of the anti-cultural characteristics of modernity, and this has also clearly shaped his late pessimism, after having experienced its transformative powers permeating and corrupting all aspects of the human realm from art, to architecture, war, and science. Frobenius possessed an extremely pessimistic vision of the future prior to Spengler, witnessing the globalized and expansive characteristics of modernity, he had eventually argued that this could poison the whole planet and perhaps we could never witness the birth of a new culture:

For when it is considered what constantly increasing expansion the 'modern' culture assumes with its machines of motion, its news service, its economic needs, how book printing, newspaper, and telephone service draw wider and wider areas into their sphere of power, so it is not difficult to calculate in how short a time the entire habitable space of the earth will be spun over with these preparatory organs of a mechanical age and its actualities, so that no people of the earth will remain any more in the enjoyment of its undisturbed and secluded state, which is necessary in order to develop (the ideals leading to high culture].

Thus, it is clear that Spenglerian Optimism is in itself a critique of modernity, since modernity as a force is now seen as the primary antagonist in this re-imagined Spenglerian narrative. Instead of a pessimistic Spenglerian vision which pushes each culture against the other, all separated like Leibnizian monads, the optimistic vision emphasizes the human element found in all cultures whilst respecting their uniqueness. The spiral unifies all cultures in a fight for their sovereignty as cultures against modernity. As John Farrenkopf argued, the early Spengler hoped that a future culture would emerge but was aware that this was contingent on the collapse of modernity to pave the way for a “non-modernistic spirit to take root”. That is, if that collapse does not itself lead to the eschaton, or the fulfillment of multiple eschatological realities materializing Ragnarok, John’s apocalypse, the Kali Yuga, and the end of the Mayan great cycle all at once.

On the possibility of a new culture Clark asserts that the new birth cannot be “imagined before-hand”, and could occur almost instantaneously, or is “happening already”, that is, the emergence of a new world-view and conception of the universe that is different from the Western, Magian, and Apollonian forms. He also argued that the birth of the new culture would need to occur far away from current existing cultures and civilizations, which is indeed a plausible argument. Especially considering the fact that some cultures have been born in close proximity to older cultures, the Magian, the Faustian Western, and a potential new Russian culture. Yet, some cultures have also been born in isolation from other cultures, such as the Chinese and the Mesoamerican cultures. But perhaps what fascinated me the most about Clark’s argument here, is his rejection of Virgil’s conception of humankind, that is, humankind as a single oikoumene that share one destiny within Earthly existence. Rather, Clark envisions a future filled with successors, who if possessing a Spenglerian conception of history will look back at our on specific times and view the birth of their own new culture with the gift of hindsight, which we ourselves cannot comprehend yet due to the relativity of time—history, and culture. I describe Clark’s rejection of Virgil as an interesting precisely because the most elaborate and profound example of Spenglerian optimism to have been materialized recently was one where the author named his new Spenglerian culture using an eponym from Virgil’s magnum opus, namely, the Aenid. The author, who goes by the username Tree of Woe, describes the emergence of a new possible civilization — the Aenean Civilization — that embodies the shift from “infinity”, as expressed by the Faustian Western culture, to “liminality”: the affirmation that humanity stands at an existential threshold — liminal space. Realizing liminal space, means to possess a position of eschatological realism, believing that humanity could perish, whilst finding the hope necessary to transcend such realities. Thus, somewhat like the Magian culture, the Aenean civilization is somewhat dualistic, based on the duality of “destruction and destiny” and “depletion and rejuvenation”. First off, the author here gives us a perfect glimpse of what Spenglerian optimism would look like in practice, and I advise everyone to read his impeccable work on this specific topic. Yet it is ironic that the author himself names the civilization after a character from Virgil’s epic, who is not only a character from a now dead civilization, the Greco-Roman, but also from Virgil himself who possessed a view of mankind that is incompatible with the Spenglerian model (the problem with this becomes clear when realizing that all of the eponyms used for Spengler’s cultures emerge from the cultures themselves, Faust and the West, Apollo and Greece, the Magi and the Judeo-Christian-Islamic culture, Spengler also compared the tragedy of the Prophet Job to the Magian culture as a whole), as Clark argued: “We need not suppose, like Virgil, that humankind is a single thing, to be redeemed from the Iron Age by divine fiat”. I say this because although the author constructs a powerful futuristic vision based on Spenglerian optimism, the vision in itself is flawed. Which is only a natural mistake, that had already occurred to many bright minds in the past. Kant for instance had inaugurated the field of speculative philosophy of history within Western thought —designated the field’s subject matter, possible units of analysis, and objective, yet produced a philosophy of history that was not perfect when compared to the model produced by his student, Herder. The reason why this specific vision is flawed, is because it does not adhere to Spengler’s model of cultural development. In other words, the author did not take into consideration Spengler’s laws when drawing his own vision. For instance, if an Aenean civilization is emerging, and it is an organic high-culture, it should have a specific ecological origin or homeland from where it derives its respective prime symbol, ethos, and spirit. There does not seem to be any specific ecological origin to this culture, at least not an organic one. There are also specific indicators of a potential high-culture that are quite straight forward, such as the emergence of a new artistic, architectural, religious, or political form, or even new methods of disposing the dead — such as the case of mummification in Egypt, the Towers of Silence in Persia, cremation in India and Greece, and several other forms connected to other unique cultures. Additionally, when a specific architectural form is presented, it is essentially not a unique one, but rather, a modern Western form. That said, the author describes the form as one which does not emphasize straight lines, or Faustian verticality, but instead orients towards “arches, gateways, and portals” which are symbols of transition. What makes this specific argument problematic, is the fact that Spengler’s form of speculative philosophy of history, despite its deeply metaphysical framework, is a form of realism, and not purely imaginative. Spengler’s higher cultures cannot be manifested or imagined into existence, they should rather be perceived, as Spengler argued, as higher organisms that are born through a peoples connection a specific landscape—ecological origin. Of course, one can argue that the individuals within the culture, especially the ones of world-historical significance, possess a form of intuitive experience with their own culture, and could either help materialize specific realities (Napoleon, Caesar, Alexander), or prophecy, manifest, or foresee their own culture’s future (Plato, St. Augustine, Joachim of Fiore, Hegel, Spengler). But for that process to occur a large amount of people should be present in a specific land that could all be tangibly accounted for, that is, they should exist, for us to at least attempt to argue for their existence within a new, present, or older, culture. Even dead and buried cultures leave tangible traces behind, be it through architecture through the form of megaliths, colosseums, mausoleums, etc., or through texts and scrolls, and even at times different artistic expressions. The cases for new cultures has been made in the past, and the present, Spengler himself has famously argued that a new culture would emerge between the “Vistula and Amur”, that the Slavic and Turkic peoples have an intrinsic connection to. Immediately one cannot help but notice the emergence of a new architectural form as an expression of a new world-view and culture, perfectly embodied by the Russian Orthodox cathedral. Others have additionally argued that a new culture is emerging in what could be called "the Aridoamerican plane”, with the new unique prime symbol of the “radiating sun”. Even here, we witness the emergence of new architectural expressions, that are both tied to the land and people, and reflect the emergence of a new world-view. Thus, I cannot help but ask, if the Aenean civilization exists, where are its own unique architectural expressions beyond the hyper-modern forms presented in the thesis? Moreover, beyond architecture, one of the most critical indicators of a young culture is the birth of a new religious form, and of course being clearly aware of this, the author (Tree of Woe) did not hesitate in speculating what this new religion would look like, again, in a truly creative manner. Yet even then one cannot help but ask whether these realities are actually coming into fruition, or just speculative flights and extremely optimistic imaginations. In the case of Russia, both the ancient elemental paganism — Rodnovery — and Orthodoxy seem to be on the rise. In the Aridoamerican plane, a new form of religiosity seems to be emerging, albeit one that is clearly still in the syncretic state as seen clearly with the cults surrounding Lady of Guadalupe. Prior to continuing, it is crucial to highlight the fact that the author himself does occasionally mention how “highly speculative” his own conceptions of Aenean culture and “liminal religion” are, the latter he described as an “imaginary reconstruction” and the former “remains an emergent ethos, not yet realized and possibly never to be realized at all”. Concerning the possibility of an Aenean civilization and religion, the author said:

At present both these systems of thought are nothing more than houses of cards built atop windy summits. They are as real as the St. Louis Arch on the moon.

Thus, what seems to be occurring here, with the case of Aenean civilization, is a projection of a future mini-golden age that could ensue prior to the end of Western civilization, and not a new culture per se. That is, an optimistic imagination of the fulfillment of Faustian culture through the rise of Caesarism, a Second Religiosity, and the final expression of the Faustian soul through grand-scale engineering and technological projects. The author also explicitly states this, and said “the Aenean soul is not merely the successor to the Faustian; it is its redemption”. In my judgement the Aenean phase, is the final form of the Faustian, one that resolves the Western culture’s obsession with the infinite through liminality, which is only possible through a Second Religiousness, one that has already, and is still, taking place in the West. The Aenean soul, or reality, is thus the swan song of the Faustian West, and not a new Spenglerian high culture.

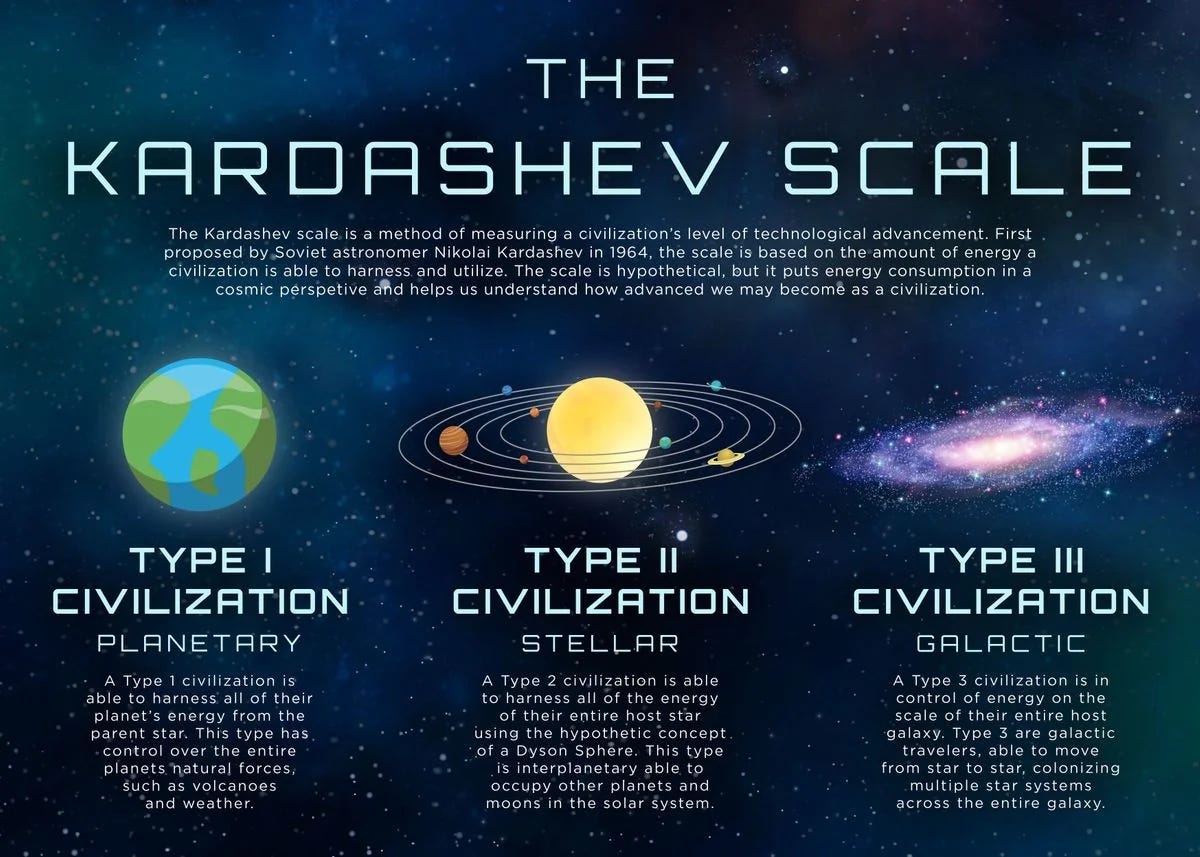

Yet one cannot dismiss such arguments without considering other types of cultures, or modes of human organization, that Spengler has mentioned across his work. Although Spengler’s work focused on high-cultures, or what we could call a type-d culture, as opposed to the three former primitive types of spiritual and psychological existence: Type-a cultures, or the age of lava, the inception of the human race spreading across the surface of the earth like lava. Type-b cultures, during the crystal era, symbolizing the crystallization or awakening of the human psyche, here the first forms emerge. Type-c cultures, which Spengler spent most of his last years exploring, are what he called Wanderkulturen, wandering or amoebic cultures that were mobile and which preceding the more static-fixed higher cultures that are the subject matter of his Decline of the West. The third “amoebic” type of cultural organization is based on an organic existence, producing languages, individual awareness, tribal collectivity, and artistic forms. Spengler named three Amoebic cultures, Atlantis, Kasch, and Turan. Beyond these are the type-d higher cultures that all descend from previous Amoebic cultures. It is crucial to mention here, that Spengler also questioned whether a new typus of culture could eventually emerge as the most evolved form of human collective existence. What we might call a “type-e culture” the late, and extremely pessimistic, Spengler eventually rejected. However, though Spengler just briefly toyed with this idea, what would have such a culture looked like? Nikolai Kardashev devised the Kardashev scale which presents different possible types of civilizations that could evolve out of our current one which could give us an idea of what that would look like if emergent from our current modern technological paradigms. The first possibility is a “Type I” civilization, that is a planetary civilization which hypothetically harnesses the energy and resources of the planet as a whole. William Irwin Thompson also argued for the possibility of an emerging planetary culture. This is then followed by a “Type II” civilization which is stellar and moves beyond the planet to harnessing the energy of stars through the use of “Dyson Spheres”. The concept of a “break away civilization” is essentially a Type II civilization that splits off, and disconnects, from the planetary civilization. Finally, the “Type III” civilization is a hypothetical civilization that moves beyond planets and stars to include whole galaxies. The concept of an Aenean civilization is one that is still based on the current modern Faustian Western paradigms, and this is clearly seen with the primary objective of the civilization, namely, the “colonization of Mars”. If such a civilization does attain stellar existence, and does indeed evolve into a new typus of culture, then the concept of an Aenean civilization here could be a reality. Yet even then, one would have to question whether such a civilization would not evolve into another mode of collective existence, but remain in the old mould (high-culture), and eventually either die out, as all high cultures do, or remain in a state of perpetual repetition, a sort of eternal recurrence albeit within a Bishop Ring rotating across space meaninglessly. The other possibilities beyond the decline of the West, for Spengler, were either, continuations of the Spenglerian high cultures, such as a possible Russian-Slavic-Orthodox culture, or the other high cultures we are attempting to imagine with the Spenglerian Optimism project. His last prediction, which we have mentioned earlier, is modernity’s war against nature reaching a climax-crescendo with a cataclysmic end, a bang, a natural and cosmic apocalypse. The series of high-cultures stops, and history ends.

All in all, the argument I am attempting to put forward here, is one that considers all the different scenarios when constructing an optimistic Spenglerian narrative. That is, the possibility of continuity of higher cultures in a postmodern world beyond the decline of the West, one or several cultures. Additionally, the possibility of a new typus of civilization, or a break away civilization as well suggesting the continuity of both the older higher cultures and the newer evolved forms. Finally, it is crucial to remember that the project is not only a predictive one, attempting to foresee the future, but also a retrospective one since Spengler argued for the possibility of retrodiction as well — the rediscovery of lost cultures in history. Thus, one can also attempt to sketch a narrative that re-explores hidden cultures of the past, and yes, many would be surprised, but there are many. These cultures, despite being dead and buried, deserve to be heard and given their rightful place amongst other higher cultures. Some have reached the status of high-culture, albeit briefly (Celtic?), whilst others have had the potential to evolve into one, but were either murdered by another culture, or their growth was hampered due to natural reasons (natural disaster or extreme climates, Polynesia, Eskimos). In the next contribution the series I will be going through Toynbee’s concept of abortive and arrested civilizations which will be extremely beneficial to the project as a whole. This might also mean covering Toynbee’s concept of “fossilized” societies, and Spengler’s concept of “wandering-cultures” and its application on some cultures that have emerged alongside high-cultures (Jewish culture embodied in the story of the Wandering Jew, or the Romani Gypsies with their prime symbol of the Caravan). Additionally, and more importantly, we will cover Clark’s concept of “Hidden Cultures” and how this could potentially assist us in identifying hidden cultures among us today, as well as his concept of “New Beginnings” and how it ties to Spengler’s necessary stages, or seasons, of cultures.

I'd argue the "Liminality" of Clarks Aenean civilization is actually more in line with the Aridoamericans which percieve space as. I agree that this likely is the final form of the west, as most it comes from America, the eastern and European America.

The Arch, much like how it was built may actually be an attempt to show the American "Eternal Horizon" by emphasizing a hollow center to see the actual horizon, which I view as a transitional between Infinite Space which envisions the infinite and Radiating Sun which realistically is an all-encompassing horizon. The true liminal space comes from standing alone in a desert/empty land, or true liminal space. I might add quite a bit of aridoamerican archetecture resembles liminal space horror/art quite a bit, whether with Taos pueblo, the average spanish mission or catholic chapel which are increasingly built away from the town square and instead

surrounded by nature.

Global optimism is a key component of worlding. Fear follows. It fear leads that is bad worlding.