Spenglerian Optimism: The Spiral Beyond the Ouroboros

Modern historiography, and perhaps academia as a whole, is suffering from the curse of overspecialization and disciplinary “tunnel vision”. This unnatural dissection of modes of knowledge has led to developments in some fields, but has rendered others obsolete. The crisis in the humanities is a direct result of this phenomenon, and when taking into consideration the crisis it is also important to note that history as a discipline has been the fastest declining major throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. The tragedy of such an occurrence lies in what the historicists called “the historicity of all things”, the fact that humans are historical beings. In my own research in philosophy of history, I explored the rise of postmodernist philosophy of history, and their respective theories—conceptions of history and time. Which I describe as the intentional detachment of modern man from time. The past is no longer to be seen as accessible to us at the present, some have gone far enough to argue that the past in itself is not real. I began my research in order to locate the works of Oswald Spengler in modern Western thought, only to be faced by what Spengler called the "unhistorical" and timeless being of modern man. Spengler is a product of historicist tradition, although he himself would not have agreed with the label, beyond the system building, generalizations, and predictions, he did share many characteristics with German historicists. The dynamic nature of Faustian culture leads to a historical awareness and instinct that exhibits severe dynamism. Regardless of the attempt by postmodernists to eliminate or kill the ontological past, the historical being of man affirms a past-present-future continuum. If modern historiography and philosophy of history denies this, this reality reveals itself in different forms in a culture, be it through art, politics, or spiritual forms.

Although Hegel's overarching philosophy of history is flawed, he does shed some light on this specific temporal phenomenon. The problem with Hegel's philosophy of history, a problem also found in Kant's own speculative philosophy of history, is the fact they were both external observers and not historians proper. However, as philosophers, they allow us to comprehend what distinguishes speculative philosophy of history from normal history, and other fields, and the objective of philosophical treatments of history. That said, as philosophers of progress, they impose their own model upon history as a whole, hence the interesting yet enforced and odd philosophical treatments of history they have produced. Despite that, Hegel's philosophy of history does provide us with some interesting insights that allow us to make sense of many Spenglerian concepts. Regardless of the spiralling nature of Hegelian history, or the cyclicality of Spengler's model, both affirm the directionality of time. The vantage point of the modern man, as Hegel argued, allows him to make sense of history as-a-whole. That is, hindsight does not only allow us to construct such philosophies of history, but to also make sense of it, hence, "the owl of Minerva spreads its wings only with the falling of the dusk". Hegel affirmed a past-present-future continuum, his speculative philosophy of history is powerful to a degree that he has accurately predicted the political rise of the US empire centuries ago. Though he had been quite careful in making predictions based on past patterns, and rather focused on present analysis when it came to his philosophy of history. The problem with Hegel however is his cultural commitments, and acceptance of a false paradigm, as Spengler argued, he was a prisoner of his culture. Hence the narrow scope of his philosophy of history when compared to Spengler and Herder, he cherry-picked the cultures that favored his own specific scheme, whilst Spengler and Herder did not only take into consideration more cultures, but their own models could accommodate more cultures and time periods.

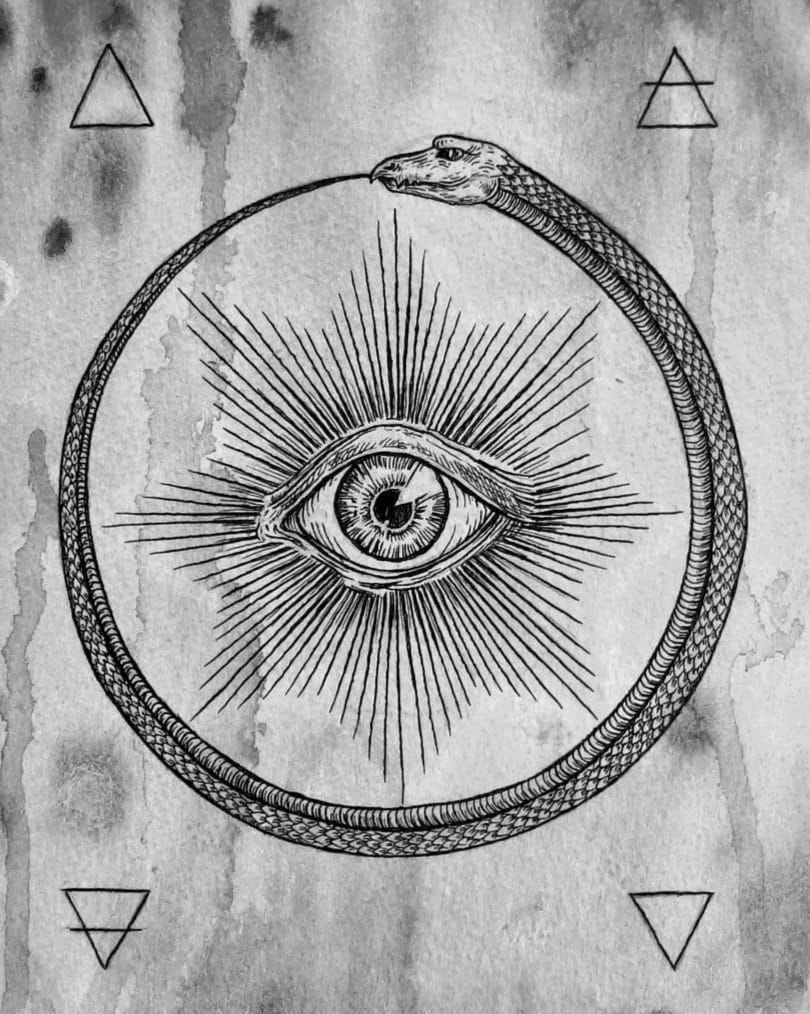

That all being said, when taking into consideration the directionality of time, beyond the natural cycles, the vantage point of the present in relation to our vast past, is somewhat unique. I say this with a degree of relativism, without trying to highlight the "special position" of modern man in the way progressive Enlightenment philosophy makes us believe. In fact, although Hegel provided a hint of this, most Enlightenment philosophers with their universalism have oddly enough led to an inversion of this idea, their flawed concept of progress leads to a misunderstanding of this historical vantage point we possess. To really grasp this idea, our unique historical vantage point, we need a position of Spenglerian relativism, and I would add a dash of optimism—something that was lacking in poor old existentialist Spengler. We have to understand that the trauma that Spengler endured was necessary for him to construct his philosophy of history. Likewise, a position of Spenglerian optimism is not only dependent on the previous pessimism, since both necessitate one another as a duality, but is also shaped by trauma albeit of a hypermodern form. Spengler’s first philosophy of history in The Decline of the West was an embodiment of his pessimism, conquered by Nietzsche’s eternal recurrence— the ouroboros , he could not spiritually transcend the zeitgeist. As Ernst Troeltsch has argued when discussing the “crisis of historicism”, the relativity of historicists combined with the effects of modernity has ironically destroyed the spiritual and moral claims of the West, and paved the way for what Nietzsche termed “the death of God”. The crisis was so profound that the it led to the rise of “crisis theologians”, Barth, Bultmann, and Niebuhr, who have developed an extremely pessimistic understanding of human nature and history, combined with a negation of modernity, and an emphasis on the otherness of God. Troeltsch, however, was still optimistic about the modern West even beyond the First World War. Yet in hindsight we realize that this optimism was misplaced, and ill-timed, Troeltsch was in denial of the zeitgeist, unlike Nietzsche and Spengler, and the crisis theologians who have immersed themselves in it.

In his writings on philosophy of history Karl Löwith has shed light on the eternal clash between two perennial concepts, or notions, of time, the pagan cyclical idea of time, and the monotheistic eschatological-directionality of time. In tracing the development of philosophy of history Löwith had discovered that philosophies of history, and the different conceptions of time, had existed as long as man existed. Our very nature as historical beings meant that to think of questions concerning meaning and pattern in history, namely, philosophy of history, was a basic human concern. What Löwith found shocking however, is that despite the proliferation and spread of the eschatological directional conceptions of time through what he called “theologies of history”, the very idea in itself in the West has been corrupted and inverted from within. Löwith thus asked, how could such Christian ideas give birth to such secular and anti-Christian ideas? With the rise of the Enlightenment the very idea of eschatological-linear direction was replaced with secular ideas of progress, the West had effectively given the birth of a deformed inverted adaptation of the divine and organic — theology of history was replaced by philosophy of history.

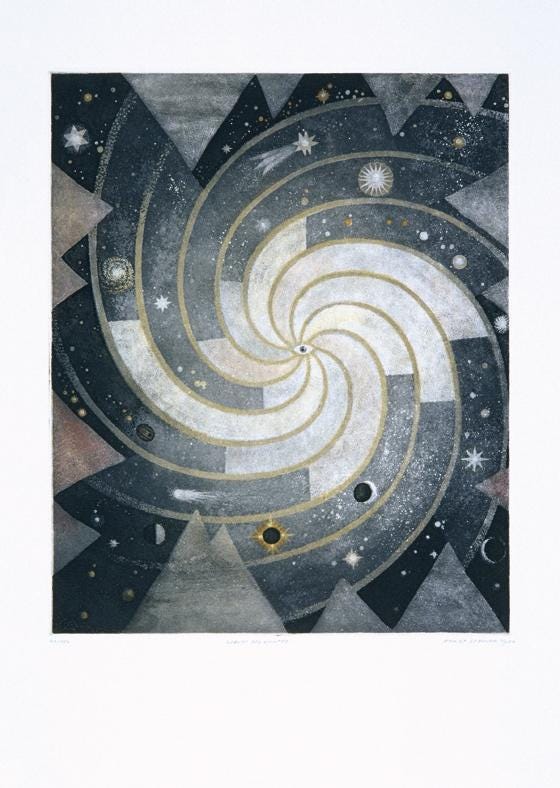

As Spengler grew older his pessimism continued to grow, the interwar period had only exacerbated his view of human nature. That said, his second philosophy of history provides a model that transcends the cyclicality of nature. Farrenkopf described it as an upward rolling spiral, Spengler combined the linear directionality of history and the cyclicality of nature and produced a spiral model. The events that Spengler endured throughout his life, and the tensions arising out of the West throughout late 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, would naturally produce this pessimistic stance as reflected by Nietzsche and the crisis theologians, this was the logical end of relativism devoid of god. It was nevertheless necessary, and destined, in a world afflicted by modernity as an exponentially growing anti-cultural force, what René Guénon called “anti-tradition”. Birth necessitates death, or what Spengler called “fulfillment”, and the opposite is thus true, a birth of a new culture—time is dependent on death and destruction. Concerning the uniqueness of our own time, every historical period and culture is equally special, but each respective age and culture is imbued with its own unique gifts and fruits as it plays its destined part in world history. The historicity of our existence and directionality of time, makes our vantage point unique in being able to connect with the farthest and most remote events in our time and history, in a manner that even the contemporaries of those specific events would have never known. As Spengler argued “much has now become history—life in tune with our life—that centuries ago was not history”. A spiral implies spiritual transcendence, beyond the natural cycles of Nietzsche’s eternal recurrence, and the meaningless march of material progress. Spengler might have not realized this, but he has effectively provided a historical model for a new paradigm shift, and one that complements a spiritual transcendence, what Karl Jasper’s called an “Axial Age”. As opposed to the state of collective amnesia man suffers from in our hypermodern age, the new age will stress the historicity of man, ultimately affirming the past-present-future continuum. Our unique historical vantage point will bestow upon us this unique gift amongst many others, through retrodiction of our remote past, we will predict and manifest a new future:

There we are sounding the last necessities of life itself. We are learning out of another life-course to know ourselves what we are, what we must be, what we shall be. It is the great school of our future. We who have history still, are making history still, find here on the extreme frontiers of historical humanity what history is. -Oswald Spengler