The past two years working on my PhD thesis I came across Rolf Gruner's paper titled The Concept of Speculative Philosophy of History (1972). Gruner's work significantly shaped my writing since he was one of few scholars who attempted to explore speculative philosophy of history as a concept, and how its rejection by mainstream academia led to a flawed definition and understanding of it. Now of course, like Toynbee, Hegel, Spengler, and Quigley, the fact that he simply mentioned "speculative philosophy of history", even though he did not attempt to construct a philosophy of history, meant that his work would automatically be sidelined. Philosophy of history proper, what mainstream academia calls "speculative philosophy of history" is essentially anathematized, even attempting to explore such a concept would risk your research as a whole. What makes this phenomenon scary, the rejection of philosophy of history, is the fact that it is an intrinsically human activity that we have practiced across history, and perhaps unknowingly, throughout our own lives. In Speculative Philosophy of History: A Critical Analysis (1968), Berkley Eddins described it as possessing:

“existential relevance,” by which I mean that it is part and parcel of basic human activity, no mere idle or luxurious speculation, but an inquiry central to the normal conduct of human affairs.

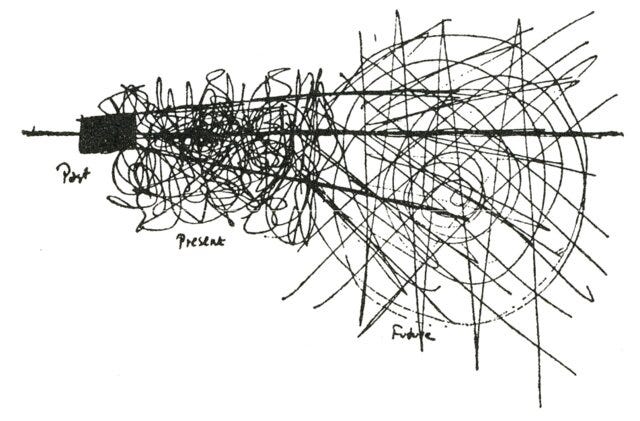

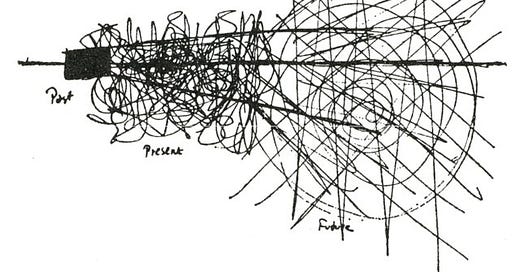

Gruner argued that philosophy of history exists because it is a basic human concern, and as long as you we exist, we will constantly question the notions of meaning, pattern, direction, and value in history. Gruner went as far as arguing that the analytical philosophers who have rejected and marginalized speculative philosophy of history, are "privately great believers in progress" and possess an implicit philosophy of history. Postmodernism also had quite the effect on the field during the late 60s and early 70s, the past was ultimately rejected disconnecting us from the past-present-future continuum. It is not a coincidence that this rejection of the past – time – has occurred at this specific stage of Western society's development, what Spengler called the "winter" phase, that is, the transition from an organic culture (Kultur) to an artificial and soulless civilization (Zivilisation). Nothing perhaps screams decline more than a culture's own negation of its own conception of time, and rejection of its past.

That being said, as a basic human concern, philosophy of history remained alive despite its rejection. There are two reasons why philosophy of history survived, the first is it latched on to the collective epistemology and continued to thrive amongst society as a whole beyond academic circles, since there was a demand for philosophy of history despite its rejection by academics—including both historians and philosophers. Spengler's work for instance was accepted by the public but rejected by academic circles since its inception. The recent revival of Spengler's work likewise occurred beyond academic circles and within Twitter circles, through Youtube videos, and works of marginalized thinkers who write on the periphery of academia such as John David Ebert. The second way philosophy of history has survived is through migrating to different fields (Sociology, International Relations etc.) what I call “interdisciplinary adaptability”, hence why adaptations of Hegel, Spengler, and Toynbee's philosophies of history emerged outside of history and philosophy departments during the second half of the 20th century. Questions concerning direction in history, its respective units of analysis, and meaning, emerged with Huntington's "Clash of Civilizations" thesis, Fukuyama's "End of History", and were more recently deployed by both Zizek and Dugin in their defense of their respective civilizations. It is no surprise that many politically and historically significant personalities were inspired by a specific philosophy of history, which they either considered or weaponized during their careers.

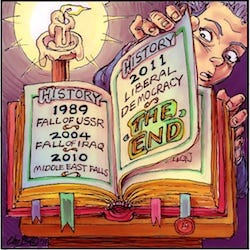

Bill Clinton was a student of Quigley, and his course on the evolution of civilizations has had a significant effect on his life and political career. Ronald Reagan paraphrased Ibn Khaldun multiple times during his presidency. Spengler's writings left an impact on Kissinger and Kennan, as well as many top officials of the German National Socialist Party to a degree that many dubbed him the "Prophet of Nazism", wrongfully if I may add (his books were eventually banned by Nazi party). Huntington's "Clash of Civilizations" and Fukuyama's "End of History", shaped Western domestic and foreign policy after the end of Cold War. The invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan could be argued to have been the result of the practical application of the "Clash of Civilizations" thesis. Israel's very existence as a nation-state is also the result of the practical application of a specific speculative philosophy of history, namely, the "Old Testament" and Evangelical reading of Judeo-Christian eschatology as philosophy of history. Iran's foreign policy on the other hand is shaped by Shia cyclical eschatology and philosophy of history, and an eschatologically affirmative form of Islam that does not separate politics from the eschatological dimensions of current developments in the Middle East. Alexander Dugin argued that a clash of civilizations will necessitate a clash of eschatologies, and if we view philosophies of history as the secularization of eschatology as Karl Lowith did, then this will ultimately lead to the weaponization of philosophies of history and their subsequent clash–convergence. I do not want to oversimplify Fukuyama's argument concerning the end of history, and simply reject his thesis through arguing that history has not ended. Fukuyama's argument is a reminder of another basic human characteristic, namely, forgetfulness, that of our recurring phases of collective amnesia during periods of relative peace and stability–a unipolar order. The last men of civilization first reject time, and their past, as seen with the postmodernists in philosophy of history, then in international relations theory Fukuyama, filled with the hubris typically seen in final stages of civilizations, argued that history has ended as the final political forms of Western culture crystallize.

History, as a directional and eternal force, what Spengler called world-as-history, synonymous with Kant's noumenal realm, has not ended, but Western culture's existence within it has perhaps ended. The state of amnesic slumber induced by the late capitalism of pax-Americana was brought to an end by the sharp turn humanity took as a result of the vicissitudes of history and time. History has not only returned, but it has never ended. Unipolar periods, when history abruptly stops, also lead to the proliferation of hubris and a blind confidence towards one’s own social, political, and economic institutions. The resumption of history’s cycles inevitably leads to an unravelling of the reality behind one’s institutions, as Toynbee argued it is the moment where the masses realize that their once creative minority has turned into a dominant minority serving their own interests rather than society. Quigley took this argument even further, arguing that a secret minority within the public dominant minority direct political, social, and economic policy behind close doors (Heathen discusses this in further whilst exploring futurism, transhumanism, and Guenon’s concept of counter-tradition). This is why the resumption of historical cycles following a historical limbo is usually accompanied by a radical change in world views, and in extreme cases paradigm shifts, as a result of the shock following the unravelling. As the society reawakens from its amnesic slumber in periods of decline, new orientations towards the past or future are born, Toynbee argued that this was a natural reaction when the possible decline, or death, of one’s civilization becomes apparent during a crisis. The result is the rise of a nihilistic futurism, embodied by accelerationists today such as Nick Land, Curtis Yarvin, and Reza Jorjani (Maverick discusses different forms of futurism and blends of both archaism and futurism in this article), or a reorientation towards the past, in the form of archaism, through an idealization of the past, which has also been materializing across the social fabric in the West. Toynbee argued that both approaches though natural speed up the decline, the former through sociopolitical and technological “flying leaps” and utter disregard for the present. The latter through idealization of the past, leads to revival of old forms and subsequent ossification of a society. Toynbee also mentions a third position, detachment from society and past, present, and future-time as a whole. Like the former two, detachment also ultimately does not benefit the society in question and leads to withdrawal from history. Conclusively, all these positions, although antithetical to one another, are similar since they are all forms of escapism.

In addition to reminding us that philosophy of history is a human concern, Gruner's argument sheds further light on the lost possibilities of this field as a result of its negligence. Such as the practical application of philosophy of history, if possible, or whether some philosophies of history overlap or clash. I have been wrestling with the idea of overlapping philosophies of history complementing each other, or if some are mutually exclusive and would inevitably clash. The former idea I explored through a parallel reading of Spengler, Toynbee, and Quigley, since the three adopt similar units of analysis, higher-cultures or civilizations. One interesting thing we can initially notice is the difficulty of escaping one’s own zeitgeist, each author was a product of his own time in a sense, despite attempting to transcend their own respective time with a relativist approach to history and culture. Although locating Spengler amongst the different philosophical traditions is a difficult task due to his unique methodology and overarching philosophy, he was clearly a product of German existentialism. Toynbee, although rejected by many empiricist professional historians in the anglophone world, labelled his approach as an empirical and scientific one. Finally, their American counterpart, Quigley, is of the American pragmatist tradition. Yet, despite their different philosophical traditions, their engagement with macro-history and civilizations that exist in the longue durée, allows their theories to transcend the spirit of their own times as reflected by their timelessness today. As I discussed above, through a Spenglerian lens the rejection of philosophy of history in Western thought is not surprising. The same is true of Quigley’s philosophy of history, in The Evolution of Civilizations (1961), he described how the changes occurring in Western universities, as well as other institutions and industries, was a result of the West entering its “crisis-disintegrating” stage. One of the most fascinating and powerful notions of Quigley’s theory is what he called “instruments of expansion”, the social tools that pave the way for the growth of a civilization. Quigley’s use of instruments of expansion reveal the internal dynamics of a civilization as it grows, saturates, and declines. This pragmatic approach, which is quite American in my judgement, devoid of Spengler’s metaphysical language and approach, is less deterministic and allows for a possible practical application of such theories. Quigley argued that the social instruments initially responsible for the growth of a respective civilization, universities, armies, ministries, eventually become institutionalized. When social instruments become institutions, and they all eventually do according to Quigley, the organization’s effectiveness begins to decrease as it loses its original function and purpose. Usually this becomes apparent to outsiders who start rejecting the institution through reforms which ultimately leads to internal conflicts. Quigley has seen this social phenomenon appear in American educational systems of his own time, today the institutionalization of education has become more apparent as well as the resistance against such changes. I would also argue that the marginalization of philosophy of history was also a result of the institutionalization of universities, and the philosophy of history was incongruent with the scientific paradigms adopted by institutionalized universities of the 20th century, and thus it failed to gain the intellectual respectability by professional academic institutions.

The social sciences were accommodated however, and with that we witnessed philosophy of history’s “interdisciplinary adaptability” and migratory traits at play, from sociology departments we have Sorokin Social and Cultural Dynamics which is a concealed philosophy of history in a scientific guise. The father of positivism, Auguste Comte, in his quest to unify the sciences realized that history and the humanities were incongruent with scientific paradigm, and required “scientificization”. What was required was a science exploring human phenomenon with the ultimate science, physics, as its inspiration, as a perfect science that has found its respective subject matter and effective methodology. “Social Physics” was the initial name given to this new science, what eventually became sociology. It is also ironic that Comte himself constructed his own philosophy of history which followed his law of three stages. Another social phenomenon in academia as a result of institutionalization, and professionalization, is what Spengler called overspecialization, the compartmentalization of knowledge into departments and cubicles. This has of course led to developments in many fields, since it led to a narrow scope of research necessary some breakthroughs, including history and archaeology perhaps. Yet, the dissection of modes of knowledge, and further, enforcing a scientific methodology on the human oriented disciplines has also led to adverse consequences in the humanities, ultimately leading to the clash between humanistic and scientific disciplines and subsequent crisis in the humanities. The result of imposing a scientific methodology on history, despite many thinkers advocating for the autonomy of historical methodology, has led to flawed periodization models in Western historiography and the loss of meaning in history, and worse, the lack of practical implications and applications of history—historical tools of analysis. History became useless, and it is no surprise that it is one of the fastest declining majors today. Realizing that we are historical beings, inseparable from history as our past, and history as a past-present-future continuum, reveals the dangers of such developments in academia and society. Asides from reminding us of our historical existence, philosophers of history like Spengler and Quigley emphasized that there are practical applications to studying history. That perhaps through a thorough understanding of the patterns of history, one could redirect policy and action in institutions, states, or even whole civilizations, in order to increase their effectiveness, or in worst cases, prevent their decline and prolong their lives.

Thanks for a

detailed and informative l article. As someone currently halfway through the second volume of the decline, it is very timely.

Thanks for this. Agreed about Sorokin, but I would never call Spengler an existentialist. His philosophical debts are to the near-obligatory neo-Kantianism of late 19th century Germany. I will look up Gruner and Eddins, as they are unfamiliar to me.

It is a hopeful closing note that philosophers of history might have some influence on contemporary events, perhaps even pulling a civilization back from the brink. Perhaps Dugin has something like this kind of influence in Russia. But cutting through all the noise amplified by social media is not something most philosophers are cut out to do. Of course, there are well connected academics at major universities with policy influence, but they belong to the cohort of thinkers who have rejected speculative philosophy of history.